Acording to the will left by that eccentric old lady, Miss Nan Corliss, her nephew, Dr. Corliss,—whom she had not seen for thirty years,—was to receive the old house at Crowfield. His wife inherited all the furniture of the old house, except what was in the library.

John Corliss, the only grandnephew, was to have two thousand dollars to send him to college when he should be old enough to go. And to Mary, the unknown grandniece whom she had never seen, Aunt Nan had declared should belong “my library room at Crowfield, with everything therein remaining.

My library room at Crowfield, with everything therein remaining.

Mary was now going to see what her library was like, and what therein remained. She drew a long breath, turned the key, pushed open the door, and peered cautiously into the room, half expecting something to jump out at her. But nothing of the sort happened. John pushed her in impatiently, and they all followed, eager, as John said, to see “what sister had drawn.” Dr. Corliss himself had never been inside this room, Aunt Nan’s most sacred corner.

What they saw was a plain, square room, with shelves from floor to ceiling packed tightly with rows of solemn-looking books. In one corner stood a tall clock, over the top of which perched a stuffed crow, black and stern. In the center of the room was a table-desk, with papers scattered about, just as Aunt Nan had left it weeks before. On the mantel above the fireplace was a bust of Shakespeare and some smaller ornaments, with an old tin lantern.

[Left, a postcard from the day reads: “This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it.]

But she meant to be kind, I am sure. I never knew why she refused to see any of her family, all of a sudden—some whim, I suppose. She came to be a sort of hermitess after a while. She loved her books more than anything in the world. It meant a great deal that she wanted you to have them, Mary.

Mary was now going to see what her library was like, and what therein remained. She drew a long breath, turned the key, pushed open the door, and peered cautiously into the room, half expecting something to jump out at her. But nothing of the sort happened. John pushed her in impatiently, and they all followed, eager, as John said, to see “what sister had drawn.” Dr. Corliss himself had never been inside this room, Aunt Nan’s most sacred corner.

We’ve been so focused on trying to cover it up, hide it, ignore it, say it didn’t happen, say it’s not our fault, we didn’t have anything to do with it, that it was them, not us.

It began to have the lonesome look which a house has when the heart has gone out of it and nobody puts a new heart in. The garden was growing sad and careless. The flowers drooped and pouted, and leaned peevishly against one another.

Only the weeds seemed glad,—as undisturbed weeds do,—and made the most of their holiday to grow tall and impertinent and to crowd their more sensitive neighbors out of their very beds.

But one September day something happened to the old house. A lady and gentleman, a big girl and a little boy, came walking over the slate[2] stones between the rows of sulky flowers. The gentleman, who was tall and thin and pale, opened the front door with a key bearing a huge tag.

John Freeth

The gentleman, who was tall and thin and pale, opened the front door with a key bearing a huge tag.

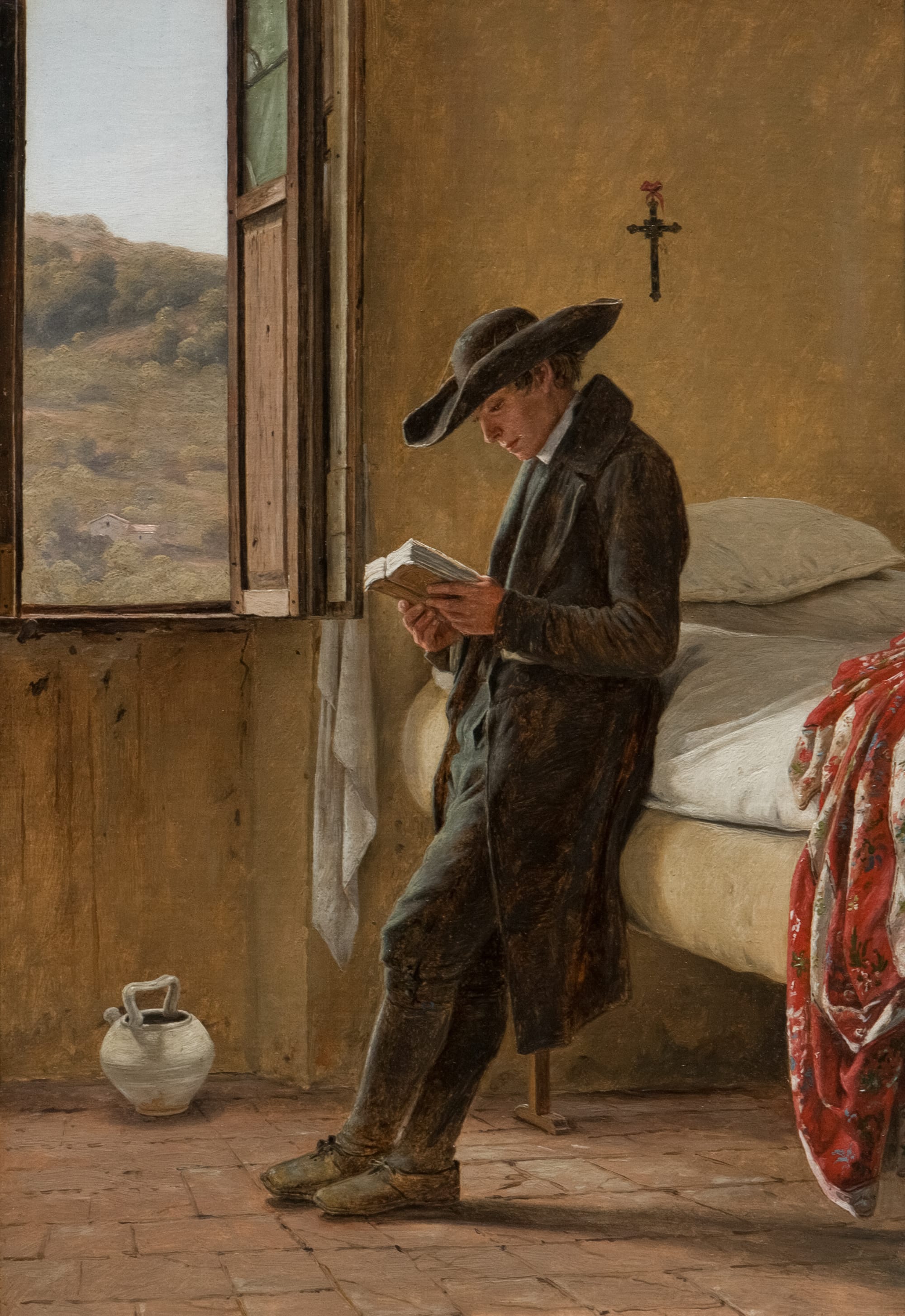

John Freeth and his Circle or Birmingham Men of the Last Century, 1792 Oil on canvas Artist: Johannes Eckstein - John Freeth (1731-1808) was a publican and poet who ran a coffee house in Birmingham (Leicester Arms, Bell Street), where the Jacobin Club.

It began to have the lonesome look which a house has when the heart has gone out of it and nobody puts a new heart in. The garden was growing sad and careless. The flowers drooped and pouted, and leaned peevishly against one another. Only the weeds seemed glad,—as undisturbed weeds do,—and made the most of their holiday to grow tall and impertinent and to crowd their more sensitive neighbors out of their very beds.

But one September day something happened to the old house. A lady and gentleman, a big girl and a little boy, came walking over the slate[2] stones between the rows of sulky flowers. The gentleman, who was tall and thin and pale, opened the front door with a key bearing a huge tag.

My grandmother’s concern when I was coming into the world was that I wouldn’t be accepted by the Black community or the white community because I’m mixed. But it’s a beautiful place to straddle—to live between worlds. I used to think of it as a bridge, but now I think of it like a tree with deep roots that allow the connection and understanding of many things and paths and people.

I managed to buy a place by the sea on the Sunshine Coast, and now I split my time between here and L.A.

I was born on Vancouver Island, in Sooke, and then moved to the interior of British Columbia for most of my childhood, to a little town called Grand Forks. I came to Vancouver in high school. I’ve lived all over the place, but during the pandemic, I got a little like, What am I doing? I managed to buy a place by the sea on the Sunshine Coast, and now I split my time between here and L.A. My kids were actually born in B.C., so it’s kind of full circle.

The Library

These old books don’t look very interesting. I want to go to college more than John does. But I don’t suppose I ever can, now.

Acording to the will left by that eccentric old lady, Miss Nan Corliss, her nephew, Dr. Corliss,—whom she had not seen for thirty years,—was to receive the old house at Crowfield. His wife inherited all the furniture of the old house, except what was in the library.

John Corliss, the only grandnephew, was to have two thousand dollars to send him to college when he should be old enough to go. And to Mary, the unknown grandniece whom she had never seen, Aunt Nan had declared should belong “my library room at Crowfield, with everything therein remaining.

My library room at Crowfield, with everything therein remaining.

Mary was now going to see what her library was like, and what therein remained. She drew a long breath, turned the key, pushed open the door, and peered cautiously into the room, half expecting something to jump out at her. But nothing of the sort happened. John pushed her in impatiently, and they all followed, eager, as John said, to see “what sister had drawn.” Dr. Corliss himself had never been inside this room, Aunt Nan’s most sacred corner.

But she meant to be kind, I am sure. I never knew why she refused to see any of her family, all of a sudden—some whim, I suppose. She came to be a sort of hermitess after a while. She loved her books more than anything in the world. It meant a great deal that she wanted you to have them, Mary.

Mary was now going to see what her library was like, and what therein remained. She drew a long breath, turned the key, pushed open the door, and peered cautiously into the room, half expecting something to jump out at her. But nothing of the sort happened. John pushed her in impatiently, and they all followed, eager, as John said, to see “what sister had drawn.” Dr. Corliss himself had never been inside this room, Aunt Nan’s most sacred corner.

A Visitor

The whistles of Crowfield factories shrieked noon before they all stopped to take breath.

The very next day Dr. Corliss shut himself up in his new study while Mrs. Corliss and Mary set to work to make the old house as fresh as new. They brushed up the dust and cobwebs and scrubbed and polished everything until it shone. They dragged many ugly old things off into the attic, and pushed others back into the corners until there should be time to decide what had best be done with them. Meanwhile, John was helping to tidy up the little garden, snipping off dead leaves, cheering up the flowers, and punishing the greedy weeds.

The whistles of Crowfield factories shrieked noon before they all stopped to take breath. Then Mrs. Corliss gasped and said:—

Oh, Mary! I forgot all about luncheon! What are we going to feed your poor father with, I wonder, to say nothing of our hungry selves?

Just at this moment John came running into the house with a very dirty face. “There’s some one coming down the street,” he called upstairs; “I think she’s coming in here.” He peeped out[18] of the parlor window discreetly. “Yes, she’s opening the gate now.”

“Let Mary open the door when she rings,” warned his mother. “It will be the first time our doorbell rings for a visitor—quite an event, Mary! I am sure John’s face is dirty.”

“I’m not very tidy myself,” said Mary, taking off her apron and the dusting-cap which covered her curls, and rolling down her sleeves.

The latch of the little garden gate clicked while they were speaking, and looking out of the upstairs hall window Mary saw a girl of about her own age, thirteen or fourteen, coming up the path. She wore a pretty blue sailor suit and a broad hat, and her hair hung in two long flaxen braids down her back. Mary wore her own brown curls tied back with a ribbon. On her arm the visitor carried a large covered basket.

“John!” cried Mary, horrified. For she thought her brother was playing some naughty trick. What did he mean by such treatment of their first caller? Mary ran down the stairs two steps at a time, and there she found John in the hall, staring with wide eyes at the front door.

It was—Something, I don’t know What, that spoke. When she pushed the bell-button it didn’t ring, but it made that. And now I guess she’s gone off mad!

“Oh, John!” Mary threw open the door and ran to the porch. Sure enough, the visitor was retreating slowly down the path. She turned, however, when she heard Mary open the door, and hesitated, looking rather reproachful. She was very pretty, with red cheeks and bright brown eyes.

“Yes, I did,” said the girl, looking puzzled. “But I thought no one was at home. Somebody said so.” Her eyes twinkled.

Mary liked the twinkle in her eyes.

My grandmother’s concern when I was coming into the world was that I wouldn’t be accepted by the Black community or the white community because I’m mixed. But it’s a beautiful place to straddle—to live between worlds. I used to think of it as a bridge, but now I think of it like a tree with deep roots that allow the connection and understanding of many things and paths and people.

I managed to buy a place by the sea on the Sunshine Coast, and now I split my time between here and L.A.

I was born on Vancouver Island, in Sooke, and then moved to the interior of British Columbia for most of my childhood, to a little town called Grand Forks. I came to Vancouver in high school. I’ve lived all over the place, but during the pandemic, I got a little like, What am I doing? I managed to buy a place by the sea on the Sunshine Coast, and now I split my time between here and L.A. My kids were actually born in B.C., so it’s kind of full circle.

My grandmother

Hakone presents the complete post content on the homepage, moving away from the traditional blog design that includes only a title and thumbnail.